Ada Wordsworth: charity, Ukrainian language and favorite places in Kharkiv. Strangers Not Strangers

With the beginning of the full-scale invasion, more and more foreigners are coming to Kharkiv. They are volunteers, journalists and soldiers, who decided to come to Ukraine and help here firsthand. They are people with interesting biographies and strong positions, but their stories are not available to everyone due to the language barrier.

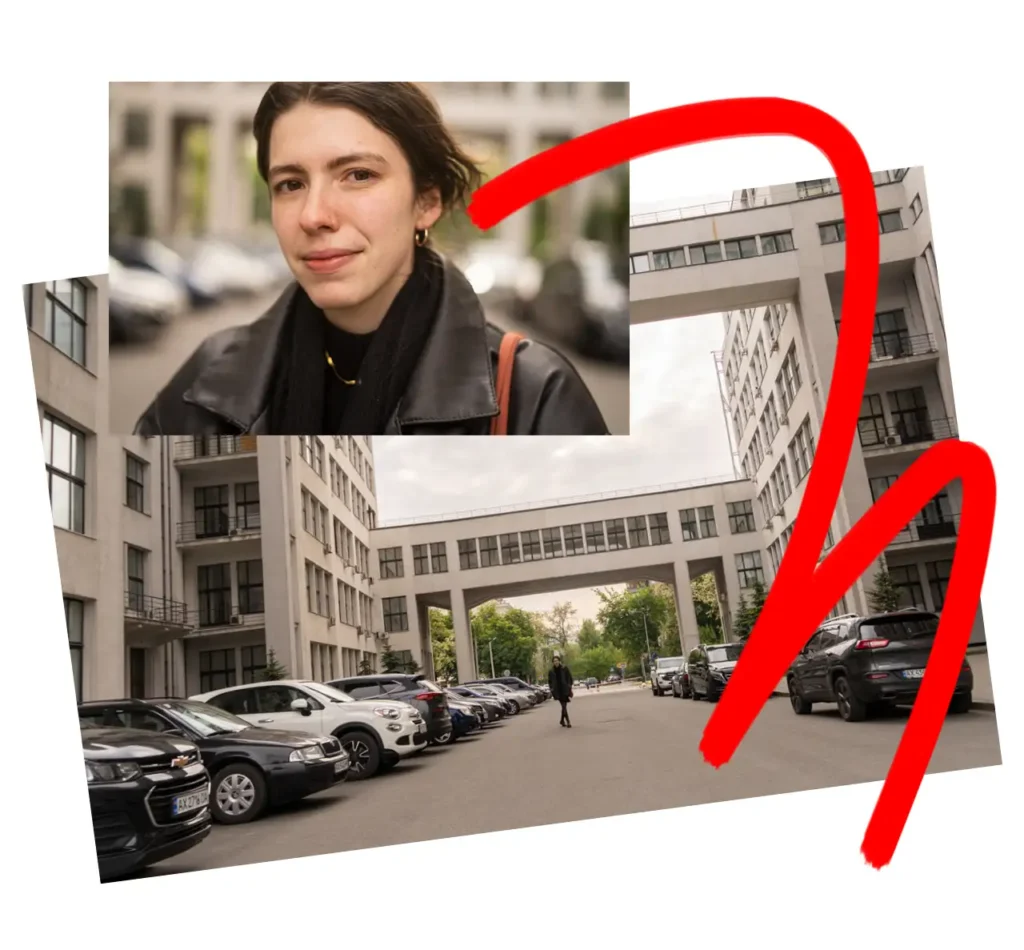

Together with Hotspot School of English, we introduce these people and their stories to you. Our third hero is Ada Wordsworth, born in the UK, London, who currently lives in Kharkiv and runs the charity foundation KHARPP.

Цей матеріал також доступний українською мовою.

«My motivation was like… you just have to do something»

— Could you please tell us more about yourself?

My name is Ada. I’m from the UK, London, and I run a charity program called KHARPP. I also write about Ukrainian culture, mostly the eastern one, and the war in general.

— Your specialty at the university was cultural studies, right?

My undergraduate was in Russian studies, and my master’s degree was in Slavonic studies at Oxford. I was studying Russian and Czech, and I was halfway through it when the full-scale invasion began.

Then I dropped out of it to move initially to the Polish border and then to Kharkiv. I came back to it last year because my university had said that I could switch from the Russian part to Ukrainian, and so ended up getting a master’s degree in Ukrainian studies.

— How did you find out about the war? And what was your first motivation to come here?

Before the full-scale invasion had begun, I was completely in denial it would happen. For I was studying Russian, a lot of people asked me: “Oh, what’s going to happen?”

On that day I was in London when it started. I went back up to university in Oxford, packed up myself, booked a flight to the Polish-Ukrainian border and moved to Przemyśl a week later to volunteer at the border.

I guess my motivation was like… you just have to do something. I’d spent five years learning Russian, and I felt that I wanted to make use of the fact that I’ve learned this language, maybe I could help refugees.

I had this idea the war would probably go on for three weeks, and then Ukraine would win. First I was just an independent volunteer, and I met a lot of people leaving Ukraine from Kharkiv. Some of them talked about their friends in Kharkiv who were doing volunteer work here and who needed money. And so we started fundraising for them, getting money from the UK, sending it to them in Kharkiv.

Later on the warfare has just escalated. I was raising lots of money and decided that I had to make a charity, had to make it official because it was too much for it to just be all this money going from my bank account. So I made a charity, called it KHARPP, which was the Kharkiv-Przemyśl project. So we were working in Kharkiv, and I’m in Przemyśl, and the idea was helping people leaving and helping people who stayed behind. And then everything went from there.

Then, in the summer, I came to Kharkiv. I was delivering ambulances and fell in love with the city, despite the fact it was also so scary, obviously, in June 2022, but I still loved it. Until that summer I was half in Kharkiv, half in Przemyśl, and then when Kharkivska Oblast was liberated in September, I moved completely to Kharkiv and lived here full-time for nine months. And it was then that I started doing repair work.

The refugee crisis had ended at that point, so I just shifted everything in the charity towards repairing homes in the occupied villages. And I guess that’s the kind of long story short of how I got here.

«Just the most beautiful experience you can have is watching a city be reborn»

— I wanted to ask you about your studying Russian. Actually, here in Ukraine we believe that the Russian language and Russian culture are Russian propaganda. Didn’t you have contradictory feelings about the war in the very beginning? Because I guess you could only read Russian sources originally.

I think it was quite black and white what Russia was. I studied Russian culture, and there was a lot of what I loved about Russian culture, very much in the past tense, but at the time, that was true. But I never had any misconceptions about The Russian State. I always knew that The Russian State was kind of a neo-fascist, imperialist state.

I think there’s also something about being British, that you recognize an empire when you come from a state which has done as many bad things as The British State. You can see when other countries are doing it, too.

— That’s very interesting. So has your opinion about Russia changed over time?

Yeah, definitely. At the start, I was motivated by guilt, I think. I felt very guilty that I studied Russian, about the fact that I’d spent a lot of time studying, I’ve been to Russia a lot of times as well. I lived in Moscow for six months learning Russia, and I felt very, very guilty about it. And I felt like I had to kind of redeem myself.

And now my motivation is that Ukraine is my home now. I feel more at home in Ukraine and particularly in Kharkiv than I do anywhere else. And the villages that I work in, I love them, and I love the people who live in them, and I like my family, and I don’t want them to suffer.

Now the motivation is just a lot more direct. I don’t have any kind of complicated feelings about having studied Russian anymore. I’m very glad that I studied it, because if I hadn’t, I wouldn’t have come here. If I didn’t speak Russian, I wouldn’t have been able to learn Ukrainian.

I guess, there’s something about when you come here. When you first come to Kharkiv, suddenly you realize that you’re targeted just as much as anyone else, so it kind of bonds you to a place, right? You become very, very connected to the place where you are. I was here in the summer of 2022, and then actually moved here in September or October that year, just after liberation. I remember all these soldiers running, and they were shouting: “The Russians are running! They’re running away!”. And it was the most amazing feeling I’ve ever had in my life.

When I first came to Kharkiv, there were only 300 thousand people in the city. And then by the time I went back to the UK to finish my master’s, there were over a million citizens, which is just the most beautiful experience you can have of watching a city be reborn. It was completely life-changing. I feel so privileged as a foreigner to have been able to come here and see that and see so much life сome back here.

— Why did you choose Kharkiv among all of our other places?

First, because of a lot of the refugees I met in Kharkiv. And so it just made sense to live. Kharkiv, I guess, was quite an easy place to be able to work.

Second, Kharkiv had so much need. There was a need in the Kyiv region, but lots of people were doing stuff there and lots of big organizations were helping there. And then there was obviously a need in Donbas.

Whereas in Kharkiv international organizations aren’t really helping that much, but we could help. And it’s kind of that middle ground where there is a need, but there’s also a possibility. And then I just fell in love with the city and then I just didn’t want to leave and so stuck around.

«Just because something was built during the Soviet Union, it doesn’t mean it has to be Soviet. It can also be Ukrainian»

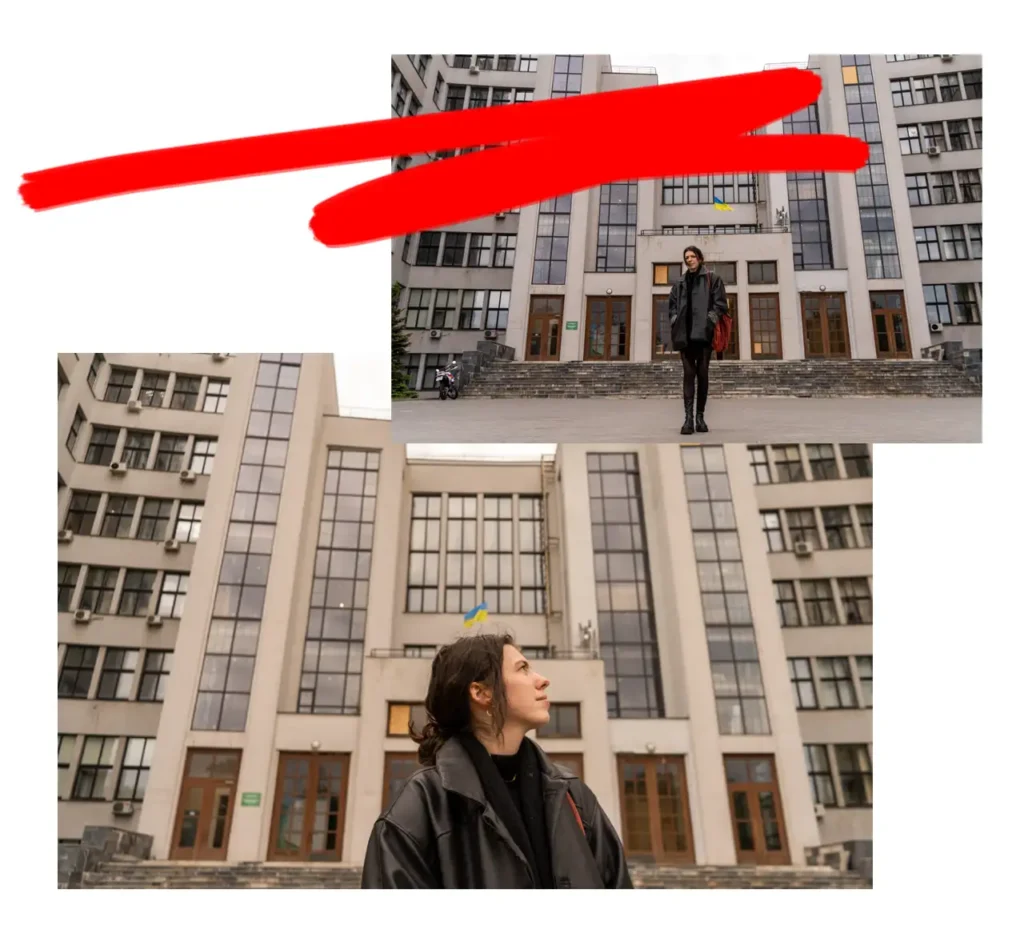

— You asked to meet near Derzhprom. And when we were walking, you also said that it is your favorite building in the world. Does it have some kind of story for you? Or why? What do you think about Derzhprom?

Fundamentalists think Derzhprom is beautiful. I remember the first time I went to Kharkiv, walking past it. I’d never seen it before. I wasn’t aware of its existence. I just knew it was the weirdest thing I’ve ever seen.

Such a strange piece of architecture… And I was taking photos of it, and this was in early summer, 2022. And the police came up to me, they took my phone and took my documents asking why I was taking photos.

They definitely thought I was a saboteur because they couldn’t believe that foreigners would come to Kharkiv and just wanted to take photos of Derzhprom because they thought it was beautiful. And so I felt we bonded in that moment with the place, being accused of being a saboteur for taking photos of it, suffered for our love. And so I guess that’s the connection.

Since then, I think, I became very interested in the reclamation of Ukrainian art and architecture from the Soviet Union and the reclaiming the idea that just because something was built during the Soviet Union, it doesn’t mean it has to be Soviet. It can also be Ukrainian.

And I think that Derzhprom is a key example of that. Because it was built in the Soviet Union, it was a symbol of Soviet Kharkiv to people in the Soviet Union. But it’s also not that. It’s also just a symbol of Ukraine. It’s a symbol of Ukrainian Kharkiv.

— Do you have any other favorite places in Kharkiv? Where do you usually go to spend your free time?

I love “Daf Pub” and the “Fat Goose” pub. I remember when I first moved here, the “Fat Goose” pub was one of the only places that was open. I respect so much that they were open at that time when things were so bad.

But my favorite place in Kharkiv is “Trypichia”, just because I think it’s the best restaurant in the world. You know, I was there yesterday. I brought my dad there.

— Wow.

Yeah, he came with me for the first couple of days. I told him “You have to come here because it’s gonna change your life” [Laughing].

And I think that whole area around “Trypichia”, around the cathedral has some of the most beautiful architecture, the most unusual architecture. And it makes me very sad that even aside from the bomb damage in places there, a lot of those buildings are just collapsing anyway because the government hasn’t looked after them and hasn’t funded them, which I think is so tragic. Yeah.

It’s so beautiful there, and I really hope that the war will make the administration here realize how important it is to preserve this architectural heritage. We’ll see.

Read more:

«You can be scared or depressed and have fun at the same time. That’s the Kharkiv experience»

— What does your family think about your living here during the war?

I think it’s obviously been very difficult for them. The idea a lot of people in the UK have is that things are very bad in Kharkiv, Kharkiv was hit nine times yesterday. But we’re sitting in a cafe and we’re talking, and it’s okay.

Like, these two realities can exist at once. And I think people outside Ukraine can’t really understand that. And my friends and family at home imagine that I spend my entire time sitting in a shelter underground and never come up and have never had fun. And I’ve just been scared and depressed for two years. And I’ve been a bit scared and a bit depressed at different points for two years, but I’ve also had a really good time.

— Okay, mom, dad, bye bye. I’m going to live in Kharkiv because I’m scared and depressed all the time [Laughing].

You can be scared and depressed and have fun and all those things can be true at once. That’s the Kharkiv experience.

Like I said, my dad’s just been here. I think it was really good for him to not just see my work, but also to see Kharkiv and be here to understand that this is a thriving city, and it’s a city which is under attack and under threat constantly, but has the most amazing cultural life going on at the same time.

— We already knew about your family. But what about friends? When you explained everything to them, how did they react?

I think it’s also scary for them and also very weird, because when I first came to Kharkiv, I was 23, and so I was at the point where me and all my friends were choosing the directions we were going in our lives. We all just finished university and were all moving in different directions. And I guess the direction that I went was slightly different.

— I’m sorry, you were just telling, like, I’m 23 and we are, like, choosing our path… And I’m just 21 and yesterday I had a very serious conversation with my grandma about why I’m not still married and have kids [Laughing].

Different cultures. Yeah, that’s also been a big shift coming here. When I’m in the UK, I feel like I’m very young. I’m 25 now and I feel like I’m very young.

I have my whole life ahead of me. And then when I go to the villages that I work in, everyone of my age has multiple children, is married, and these are different universes, but that’s okay.

«I always say I’m the only British person who speaks Slobozhansky surzhyk perfectly»

— What was the biggest culture shock for you when you came here to Kharkiv, to Ukraine in general?

Well I’m from London, a very, very big city with everything that comes with very liberal attitudes. And I guess when I came here and then immediately started to work in very rural villages, I guess, the fact that I was a young woman was slightly difficult for some of the old men in these villages to comprehend, when I turned up in my big car and said: “I’m gonna repair your windows”. And so I guess that gender aspect was a big culture shock for me, realizing that people did view me very differently.

But I don’t think that’s the experience in Ukraine as a whole. That’s not something I experienced in Kharkiv. I think it’s very much because I chose to work in very rural areas where, generally, the people who are left in these villages are much older and have a much more oppressive attitude.

What’s been really nice is that because I’ve worked in the same kind of 18 villages for the past year and a half, that’s completely stopped now. When I first went there, I did feel like I was treated very differently as a woman. I didn’t feel like I was very respected. It upset me because I felt like I’m doing so much and you can’t even look at me or speak to me or shake my hand.

But now we‘re such good friends with these old men, so it worked out. Yeah… Now I’m like one of these guys.

— You already mentioned that it was easier for you to learn Ukrainian because you already knew Russian. But what do you think, what is your level of Ukrainian right now? Like, do you understand people in the villages?

Completely. Yeah. I work entirely in Ukrainian now.

— So we could do this interview in Ukrainian?

Ну так, можна. [Well, we could]

— Окей. [Okay]

Ну що ж… [Well…]

[Both laughing]

А розмова вийде англійською чи українською? [Will the interview be in Ukrainian or English?]

— Це буде двомовний матеріал. [It’s gonna be a bilingual one]

Ну що ж, тоді можна зробити двомовне інтерв’ю. [Well, we may speak any language then]

[Laughing]

— Now, I’m ashamed of my level of English.

Oh, my God, no, your English is completely perfect. Also, the problem with my Ukrainian is that I’m very good at talking about walls, windows, train stations, and then, beyond that, I get a bit lost, when having chill conversations with people just about life.

I am like, wow… I don’t know the words…

— I have a friend, and she went here to work in the building camp. She’s a Brazilian, and she knows Portuguese, Swedish.

Oh, did you interview her? Yeah, I’ve read it!

— She lives with me right now. So she says that all she knows in Ukrainian is about building and repairs, and she knows it only in Ukrainian. She doesn’t even know what it is called in her native language.

This is what I have. I only know words about windows, about cars also.

I’ve never driven in the UK, I only drive in Ukraine. And I can go to the mechanic in Ukraine and completely perfectly talk about the inside of my car engine, I do know exactly what it is. And then, when a UK donor bought me a car, and I had to call him and explain what the problems are, I realized that I didn’t know any of these words in English. I can tell you everything about a car engine in Ukrainian but I have no idea in English.

— When you just began to learn Ukrainian, did you have some funny stories about mispronouncing something or something like that?

Hmm. I think the point is, when I started learning Ukrainian, I started learning Ukrainian in villages in the north of Kharkiv Oblast, where the Ukrainian language that they speak is very, you know, Slobozhansky surzhyk [a distinctive dialect]. So I always say I’m the only British person who speaks Slobozhansky surzhyk perfectly, and I guess I can’t think anything funny about, like mispronouncing things, but it was definitely a case that when I would then go to western Ukraine or to Kyiv, people just wouldn’t really understand what I was saying because I was speaking very much village dialect.

— What was the hardest thing to pronounce for you? Like, maybe some sounds or maybe the words.

I can’t roll my r’s, and I’ve never been able to. And so that’s just always been a problem. Like, I can’t do it. It’s not possible for me.

— Can’t you do what?

I can’t roll my r’s. Like “r-r-r-r”, I can’t do it. And every teacher I’ve ever had of Russian and Ukrainian said that they would teach me how to do it, and they couldn’t.

And then I guess there’s just an issue of words which are similar in Russian and Ukrainian but have different meanings. Switching between the languages is also difficult, but I think, the hardest thing is definitely the grammar. And I always knew when I learned Russian that my grammar was awful, and I was always okay with it.

I used to speak Russian, but I did it very poor, I made lots of mistakes, and I really want to speak good Ukrainian though. And so that was quite painful, having to learn all the grammar.

And it’s still painful. It’s still an ongoing process.

— Not all Ukrainians know the correct grammar.

Yeah. Ukrainian language makes it even more confusing because I learn something because it’s just what everyone says around me, and then I’ll say it in front of my Ukrainian teacher, and she says: no, no. Completely wrong. Makes no sense.

— What would you choose in Kharkiv? What do you really need in the city to be changed?

Oh, that’s interesting. Kharkiv could ideally be a bit further away from the border. I think it’s the main problem here.

Aside from the war, I think it’s two more things. First, the thing that I said before about the architecture — I think, the city needs to care more about its heritage.

And Kharkiv has such an amazing, eccentric architecture, so many different eras all meshed together, and that’s so wonderful, so beautiful. And it really surprises foreigners when they come here now and they expect to see war, and they actually see pre-revolutionary architecture and constructivism and everything mixed together and neoclassicalism all together. I think it would be nice if there was more care put into that and these buildings were better protected.

The other thing I was going to say is… Some parts of Kharkiv are really pedestrian, and that’s really nice. There are walkable places. You have such a beautiful square, and the fact that it’s just a car park makes me so sad. I just don’t really understand the logic. Like, you say, it’s the biggest square in Europe… Why then it’s kind of the biggest car park in Europe right now? I’d definitely change that.

Hotspot is a result-oriented school of English. They develop sustainable and conscious skills in these three aspects: grammar (to avoid nonsense in writing or speaking), speaking (to use words and rules correctly and appropriately) and listening (to understand people around and to be understood).

Hotspot’s big idea is to teach people how to study. Hotspot doesn’t just teach the language, but also helps people to love learning, which as a result might improve the standard of living in our city and country.

Interview — Arysia Chernobai, transcribing — Asya Shevtsova, editing and amends — Oleksandra Ponomarenko, photos — Katerina Pereverzeva, Yurii Kapliuchenko, cover photo — Katya Drozd